Whatever my views, we’ve decided to leave the EU and as Mrs May is now famous for saying ‘Brexit means Brexit’, so why doesn’t she get on with it?

Preparation takes time. Before negotiating even the smallest of deals, you need to be well prepared, and we’ve been advised this week of the expected additional cost and recruitment needs. Set next to 43 years of membership and integration and the time the negotiations will likely take, the period of preparation measured in months rather than years is disproportionate.

It seems that hardly a day goes by without either a UK pro-Brexiteer or an EU official suggesting that we should get on with it. There’s a gap between the unelected officials and the elected representatives of the people.

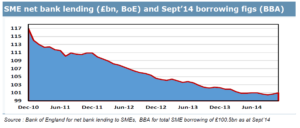

The EU, and particularly the countries of the Euro Zone, are in a mess. There’s a German hegemony that is beggaring southern Europe (under-valued German currency and massively over-valued southern European currency). There’s never been a successful monetary union without a parallel or preceding political and fiscal (read corporation and income tax) union. To state the obvious, there are the beginnings of a political union in the EU and no fiscal union. Without a single fiscal authority within the Euro Zone there can be no common monetary policy for that zone. The political will / union appears to be fracturing; the unelected officials of the EU seem to be further and further ahead of the European electorate when it comes to integration. With political union stagnant at best and possibly fracturing there’s no chance of a fiscal union.

The question becomes then how long will the Southern European countries and France put up with this, probably not much longer. In any case, the situation gets worse by the day, deficits rise, borrowing rises to fund deficits, and the need to devalue to re-balance the economies becomes worse. Or in the jargon austerity continues so that Germany can, in theory, be repaid debts that in practice can never be repaid and which must, therefore, be forgiven. Plus we may have another banking collapse, lead this time by the German banks.

The worse the mess in the EU the better the deal that the UK can negotiate and / or the less impact a so-called hard Brexit will have on the UK. Playing the long game may be playing the smart game. A ‘week is a long time in politics’* six months is a lifetime.

*Harold Wilson, UK PM 1964 to 70 and 1974 to 76.