Each day brings fresh evidence that the traditional UK banking model is under intense pressure, if not actually on the verge of breaking down altogether. RBS was on the receiving end of some elaborate media speculation last weekend that it was planning to shed a further 15,000 jobs to save £800m per annum in costs; not surprisingly, the report failed to elicit any official response from the bank in advance of it publishing its results later this month. However, that it is still in business at all, having lost a reported £50bn since its original Government bail-out in 2008, is little short of a miracle. In any other sector, losses on this scale would not be tolerated. The financial institutions, including the banks themselves, would simply call time on the business and its management.

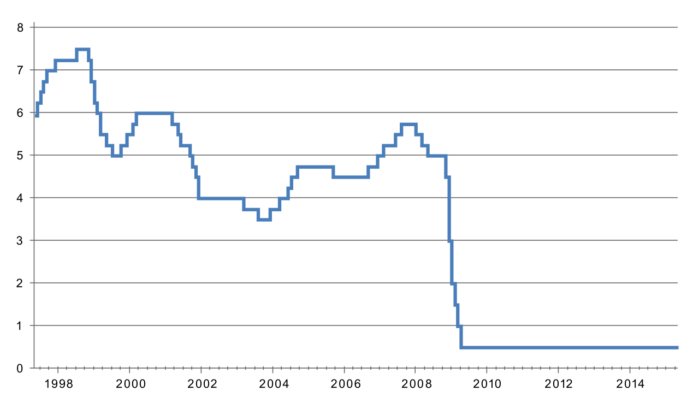

RBS clearly has some special problems, including the need to replace an obsolete IT system that is prone to breaking down, but there is one common and lethal trend that plagues all the banks – the fall in interest rates to record levels. Resulting margins are simply too fine to sustain profitable existence, which is why we also learnt last week that the Co-op Bank has put itself up for sale. Good luck with that.

Adding to the woes is the fact that low interest rates are extremely popular with politicians because, in combination with the fall in the value of sterling, they can power economic growth in this post Brexit era by helping our exporters. They also keep down the costs of borrowing, including mortgages. The irony is that, if and when interest rates do start to rise, we know from their past behaviour that the banks are likely to put up the cost of borrowing before they pass on any of the benefits to long-suffering savers. That’s how they will hope to restore margins.

It begs the question that, if the banks can’t earn a decent crust in times of low interest rates, how can they expect anyone else to, especially if they don’t enjoy the same special dispensation to make losses. The picture becomes even more disturbing when set against the backdrop of rising inflation, which we learn was 1.8% in January, up from 1.6% in December. Already, this is almost alongside the Bank or England’s target of 2% for this year and racing towards the 2.7% predicted for 2018.

The low interest rate era looks like it will be with us for some time yet and it is hard not to feel sorry for the honest savers who have just seen another 0.25% shaved off their returns from National Savings products – a move quickly reflected in bank and building society deposit rates.

What it means is that the relatively secure returns that are readily available through P2P loans are looking more attractive with each passing day.