The phrase “Neither a borrower nor a lender be” sounds both elegant and wise, but if the advice contained in those words, taken from a passage in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, were to be adopted literally, the commercial world as we know it today would come to a shuddering halt. Whether we like it or not, money is the essential lubricant for any business, regardless of size, sector and location.

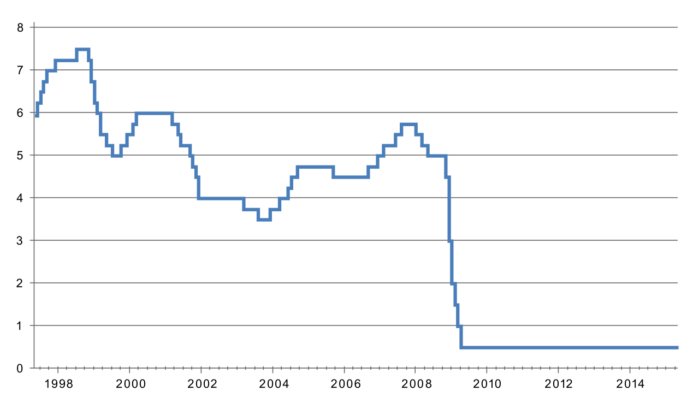

That is why there should be no shame or stigma attached to borrowing – provided it is for the right reasons and terms are sensible and fair. Right now, the P2P lending sector is awash with both individual and institutional investors eager to secure a reasonable return on their cash in the current low interest rate environment. But SME borrowers are not so plentiful, presumably because they are uncertain about the post Brexit world that lies ahead.

If that is the primary reason for lack of appetite then, if anything, the picture is becoming even more confusing as politicians, lawyers and other vested interests jostle for position on deciding the final terms of the UK’s exit from the EU. But, as those of us in the P2P sector know only too well, there is another, more apposite quote (this time from Benjamin Franklin) that says “Out of adversity comes opportunity”. The unvarnished truth is that, if the 2008 financial crisis had never happened, the P2P sector would probably never have taken root and flourished in the way that it has. So, for that, let us all be thankful.

In the meantime, SMEs, often described as the backbone of the UK economy, should not be encouraged to get themselves into debt simply for the sake of it, or just because the money is available, but to view borrowing as the gateway to growth and opportunity – to invest in people, technology, new plant, marketing, or a new products or services.

The trick, though, is to borrow on the right terms. The banks may be lending more to SMEs than they were, say, a year ago, but often this is not in the form of a straightforward fixed term, fixed rate loans. Customers are often encouraged to go down the invoice financing route, where fees can be extortionate and the arrangement can be difficult to escape from once signed.

The cost of borrowing is trending down because of competition, which is exactly the way it should be. And the ‘one size fits all type of finance’ is a thing of the past; there is an immense variety of options available if you can be bothered to shop around. That lenders will want their money back is obvious, but you don’t necessarily have to give up your precious equity, or risk losing your house through signing personal guarantees, just to gain access to the right type of finance. Alternative finance has brought genuine innovation to financial markets – it would be a pity to suffocate it with onerous regulation.