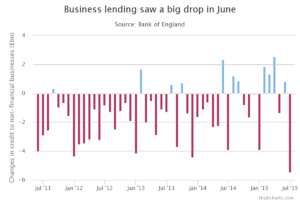

The prospect of boosted savings returns has seen traditional savers become SME lenders through Peer to Peer lending platforms. In fact they are flocking in their masses, and both the banks and building societies are running scared. The Yorkshire Building Society has taken particular umbrage at what it views as “bad investment decisions” and “would urge anyone considering riskier investments such as P2P or equity-based investment to take independent financial advice before doing so”, according to a scaremongering article in the Daily Telegraph. It’s worth noting that such “independent financial advice” can of course be received at the Yorkshire Building Society for any Telegraph readers particularly affected by what they had read.

Yet it is hardly a surprise that the banks are launching their own counter offensive: they are losing out on bucket loads of low cost capital. The implementation of the Innovative Finance ISA next year should see even more switch to P2P lending, as they will be afforded tax breaks on profits earnt through peer to peer lending platforms. This is obviously good news for all the platforms, but is better news for existing lenders who should see more security as the money comes in.

Whilst there are risks when investing through Crowdlending websites, the larger platforms are doing everything they can to mitigate the risk to ensure that they can offer savers a viable alternative to banks. RateSetter, in my view, have the best offering from the big players. They have operated a provision fund since 2010 that proudly boasts a 100% record of reimbursing investors who have lost their money when a borrower has defaulted on repaying a loan. The fund contains over £16 million, offering more than 150% cover against claims. Every borrower contributes to the fund by paying a compulsory fee when they agree to lend over the platform, and should a default occur, the money is paid back in full. Should the fund become depleted for any reason, all outstanding loans would be redirected to the provision fund and pooled repayments would be shared back proportionately to investors to ensure they aren’t fully exposed to a particular default. To put this in perspective: the government guarantees the banks at the cost of the taxpayer. Furthermore, the guarantee only pays out if the bank goes bust and then only to up £75k. If a P2P platform fails, the FCA’s rules dictate there’s always an alternate supplier who will run off the loan book.

My response to Yorkshire Building Society’s view that investors are entering peer to peer lending with their eyes closed would be to say that investors are in fact more likely to act cautiously when lending across online platforms. People should always question what looks at face value and exceptionally good rate, and should always choose an investment on the value of its security first and foremost. There are enough platforms who operate provision funds, and who also demand borrowers take out credit insurance or in some cases personal guarantees. Transparency is, and should be, prioritised above all else; it is hard for banks to argue that platforms are complicated to use when it was the banks themselves that propounded the concept of “borrow short term, lend long term”, a notion that stimulated the financial crisis and the demise of the likes of Bear Stearns. P2P lenders instead advocate a “lend for 12 months, borrow for 12 months” policy that is wholly transparent. And with no leverage used to facilitate the loans, arguably the two major structural causes of the financial crisis won’t be an issue for Peer to Peer lenders.

Whilst more money is poured into Peer to Peer lending platforms, the alternative finance industry as a whole will see some consolidation as well. The bigger companies will obviously continue to get bigger, but the consolidation will also help smaller players offering niche services to replace traditional banking facilities such as invoice discounting and property lending. The result? More streamlined, better-run companies who prioritise lender security and endeavour to minimalize the risk for regular individual investors, who can offer a viable alternative to those sick of the miserable rates offered by banks, but without the appetite for investing in the risky world of stocks and shares.

Moreover, institutions with a low cost of money, such as family offices, schools and county councils, will be drawn into investing over peer to peer lending platforms rather than leaving their money to stagnate in bank accounts. Local government treasurers would be particularly keen to lend to platforms that subsequently lend the money to constituents or local SMEs in an attempt to further support their local community. This could see an increase in localized Peer to Peer lending companies such as Folk2Folk, who operate solely in the West Country.

The result of all this? Bad news for banks, good news for savers and SMEs.